| Country | Issue Date | Tenor | Size | Yield at issue |

| Zambia | Sep 2012 | 10 years | $750 mm | 5.625% |

| Rwanda | Apr 2013 | 10 years | $400 mm | 6.875% |

| Nigeria | July 2013 | 10 years | $500 mm | 6.625% |

| Ghana | July 2013 | 10 years | $750 mm | 8.000% |

| Gabon | Dec 2013 | 10 years | $1.5 bn | 6.375% |

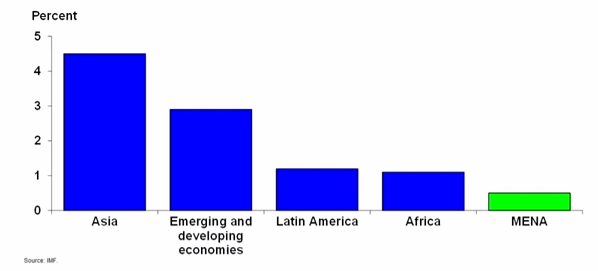

As Wheatley correctly points out, this is a Gabon story as much as it’s an Africa story. There are a lot of ways to slice this, the most immediate being yield differences. Wheatley:

Is Zambia, at 5.625 per cent (cheaper than Spain at the time), really in a different ball park from Ghana at 8 per cent? Yes and no. When Zambia came to market in September 2012, yields on US Treasuries were at their tightest and investors were scrambling for any deal that offered something better.

“There were opportunities to lock in great transactions,” says Samara. “But you still had to have a story to tell.”

Rwanda faced perhaps an even more inviting market, with investors getting so frustrated at low yields in the US they seemed willing to take almost any risk. Even in that environment, however, Rwanda had to pay a lot more than Zambia.

Nigeria and Ghana tell a similar tale of the post-tapering world: the decidedly less risk-on environment that followed comments in May by Ben Bernanke, chairman of the US Federal Reserve, suggesting the end of ultra-loose monetary policy was on the horizon. But Samara says that even in those more difficult circumstances, the right issuers have been able to get bonds away.

I would also point out the dramatic difference between these yields, and the indicative yields of their currencies at the beginning of this year, which I previously discussed here. Pasting those local currency yields into the above table gives us the following:

| Country | Issue Date | Tenor | Size | Yield at issue | Indicative FX yield as of Jan 2013 |

| Zambia | Sep 2012 | 10 years | $750 mm | 5.625% | 9.80% |

| Rwanda | Apr 2013 | 10 years | $400 mm | 6.875% | 12.30% |

| Nigeria | July 2013 | 10 years | $500 mm | 6.625% | 14.40% |

| Ghana | July 2013 | 10 years | $750 mm | 8.000% | 22.90% |

| Gabon | Dec 2013 | 10 years | $1.5 bn | 6.375% | N/A |

The debt yields are significantly lower than the FX yields reported in January (courtesy of Silk Invest). A lot has happened in the world this year to drive this divergence, but what this screams of more than anything to me is the benefit of borrowing dollars in the Eurobond market.

Put another way, let’s use the example of Nigeria, which is far and away the largest economy of any of these. In an ideal world, an economy like Nigeria should be able to draw a far larger issue size than $500 million, and denominated in naira, but if they did, they would be paying much more than 6.625%. And even in dollars, the $500 million ticket size indicates that appetite is still fairly limited, despite all the currency risk being shifted onto Nigeria (which, having some 90+% of its economy dependent on oil, is less burdensome than the task facing, say, Rwanda).

I’m all for developing local currency financing mechanisms, but what this all says to me is that there’s still a VERY long way to go.